“Money was the sizzle”: Blockchain pioneer W. Scott Stornetta assesses Satoshi’s work

Cryptographer colleagues W. Scott Stornetta and Stuart Haber’s paper “How to Time-Stamp a Digital Document,” published in 1991, is what many consider to be the first incarnation of blockchain technology. Stornetta and Haber set out to create an immutable ledger, and in doing so, they came across what they deemed “a naïve solution.” That solution relied on a central authority, a “digital safety-deposit box” that could record the date and time a certain document was created and also store a copy of it. The main problem with this method came down to trust. “Nothing in this scheme prevents the time-stamping service from colluding with a client,” Stornetta and Haber wrote.

They’d hit a dead end—or so they thought. Since their original mission seemed undoable, they attempted instead to disprove the possibility of creating an immutable ledger. In doing so, they came up with one that wouldn’t require a trusted central authority. In other words, they ended up creating a distributed immutable ledger.

At the time, the two men were working at Bellcore, a telecom research company. Three years after releasing their time-stamping paper, they went on to found Surety, the main focus of which was to offer time-stamping services using the first-ever blockchain. Instead of a purely digital ledger, however, Surety posted customer hashes in a different sort of immutable public record. It printed them in the “Notices & Lost and Found” section of the New York Times.

Today, Stornetta is the chief scientist at Yugen Partners, a private equity firm that invests in companies using blockchain technology. We recently met up with Stornetta outside of Columbia University’s business school, where he will contribute to a blockchain course for executives, to talk about Satoshi Nakamoto, cypherpunks, LUMAscapes, dairy cows, sizzle, and FOMO—not to mention what he believes is the biggest mistake blockchain project architects keep making.

You were on the cypherpunk mailing list back in the day.

I was sort of in that community, sure.

How did you wind up a part of that?

I was very inspired, for example, by David Chaum and what he was trying to achieve very early on—way before Satoshi [Nakamoto, the pseudonymous inventor of bitcoin]—with digital cash. And not just digital cash, but the whole zero knowledge proof space. In a sense, it was really the RSA people who kicked that off—the concept that one can have both a public and a private key, something that could be widely broadcast and yet no one would be able to create the same thing using the same key. That whole move to asymmetric encryption itself is a very liberating idea.

To me, that was the zeitgeist of the time. I spent a lot of time thinking about the kinds of problems that were posed, but interestingly enough, even after the “blockchain” work we did, I didn’t immediately see the connection between it and money.

How do you feel about the fact that your 1991 paper about time-stamping ended up inspiring this whole movement, which is really what blockchain is now?

That is quite frankly very humbling. It was a series of papers and a series of patents. It’s unfortunate that so few people actually read all the papers and patents, because there are quite a few ideas that can be mined from there that some have since reinvented because they never read the papers.

Any ones in particular?

I want to focus on the positive. But I guess I can capture one moment a couple of years ago when someone sent me a poster of the blockchain space. It was talking about how several billion dollars had been allocated into all of these different areas. You know, it’s one of those posters where they have the logos of all the firms…? They look very attractive…

A LUMAscape?

Is that what it’s called? You learn something new every day. It was almost like a punch in the chest. All of these people are doing stuff, and I was feeling very humbled that Stuart [Haber] and I had been at the right place at the right time to have a useful insight that laid the foundation. I don’t want to take credit for all of their work, but it did in fact play an important role.

Is digital currency a surprising thing to have come out of your papers? Would you have expected any other use cases to emerge before that?

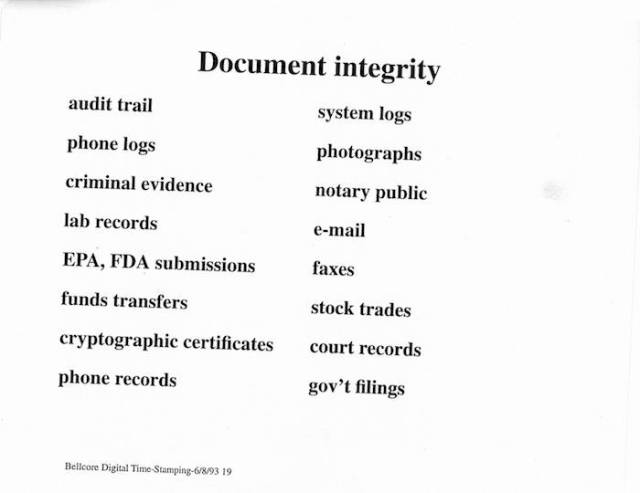

It’s funny—my wife is very good at keeping records of things. She found a slide deck of a presentation we had given in the early ‘90s to an investment firm. It lists all of the industries and examples that we thought could be affected by this [technology]. It was remarkable to me how little updating needed to be done to something that was as old as that slide. We thought what we had done [with the 1991 time-stamp paper] was pretty exciting, and yet it was hard to get a party going around it.

Slide from a presentation Stornetta and Haber gave for an investment firm in 1993 listing the areas where their distributed immutable ledger could apply. Courtesy of Marcia Stornetta.

The bitcoin white paper started the party?

Yeah, somehow it added the sizzle. In the investing world, we talk about sizzle and steak. I am still of a mind that we created some meaningful steak. But maybe it didn’t have the sizzle that it needed. Bitcoin was all about how you could get rich quick. Not that that was Satoshi’s goal, but it became that. You either write about sex or money if you want to attract immediate attention.

So money was the sizzle.

Money was the sizzle. And the fact that one could mine, that’s a very powerful marketing metaphor. It creates that apparent analogue with gold, when in fact it’s really got nothing to do with that. One of the best things Satoshi did was his branding. I’m sure it was unintentional, but the whole idea that I could use my computer to get in early on mining coins created a great—what I guess we would call a FOMO. A fear of missing out.

Yes, I’m familiar with FOMO.

I think that’s one of the threads that explains bitcoin’s rise. Certainly, there’s also a libertarian thread, of which I’m a big subscriber. But as someone that works at a private equity firm, we’re looking for great ideas that can become self-sustaining rather than just being a hope for something. We have to look at things through a lens that celebrates the libertarian aspirations, but also asks how actual economic value is unlocked in the here and now.

What does being a libertarian mean to you?

I guess I really like the idea of us all sort of being middle-class—and being in a peer-to-peer, free-exchange market and not seeing such concentrations of power and capital as we have today. It’s not that I’m opposed to them because I think only evil people are in those bastions, but it’s an inefficiency in the market. When power and capital get too concentrated, it leads to not treating people as peers.

You don’t think it’s only evil people in those “bastions,” but do you think it’s easier to get to those top tiers if you are evil?

Not necessarily. The problem is that good people get there, and they are easily corrupted. We all are easily corrupted. What’s that Socrates quote? “With virtue comes wealth, but virtue does not come from wealth.”

I noticed that you tend to quote a variety of sources when you’re writing. I believe you quoted The Princess Bride in a piece you wrote for Coindesk in December?

The Princess Bride definitely figures into my worldview, that’s for sure—as does Monty Python and the Holy Grail. Star Wars figures in. My training is as a physicist, on the theoretical side of physics. There’s a joke that’s told about physicists, both at their expense and told with delight by physicists. Maybe I can just tell the joke and then draw the conclusion about why you ask why I quote from different sources?

Okay.

There is a dairy farmer that is not getting the milk production he’s expecting from his cows. He decides to call in three experts to solve the problem. One is a psychologist, one is an engineer, and one is a physicist. First the psychologist goes in and writes up her report. She says the cows need to relax, and to do that you need to paint the barn’s interiors with more pastoral settings. The engineer comes in and says that the diameter of the tubes leaving the udders is too narrow, causing turbulent flow. Making the tubes bigger will increase the flow of milk. Then the physicist comes in and analyzes the situation, and says, “Well, I’ve got a perfect solution, but we’re going to have to assume a spherical cow.”

Physicists tend to want to look for a deep, underlying solution that abstracts out the details, because if you consider all the details, then you’re not really getting at what the essence of the problem is. As a result, I think that many quotations help to get at the essence of issues.

How do you think that sort of thinking applied to your 1991 paper “How to Time-Stamp a Digital Document”?

I think it very much applied to it because our original intent was to create a kind of immutable record. We found our original solution unsatisfactory because it relied on having a central authority that one had to trust. While in a pragmatic sense it was for many uses an adequate solution, it seemed to lack any elegance that spherical cow thinkers would like, or that Stuart as a mathematician would find satisfying.

After reaching that level, we went on a quest to see if there was a way we could eliminate the trusted central authority. In fact, what happened—I’ve told this story, but it’s one of the few good stories I know, so I have to keep repeating it—was we finally decided it couldn’t be done. To make sure we could get a publication out of our work, we said, “Why don’t we prove it can’t be done?”

It was in the course of proving that it couldn’t be done that we stumbled upon the solution. If you have two parties involved in a transaction and they want to collude, then you need a third party to detect the collusion. But then what if that third party becomes part of that collusion? Then you’d need a fourth party, and so on and so forth. Our proof was saying this problem can’t be solved because it would involve a conspiracy so large that the whole world would be in on it.

It was then that we realized that was in fact the solution. Because if the whole world is in on a particular agreement about what is real, then that’s what’s real. By linking the record and then widely distributing it, we could have all the world as witness of a common ledger, a common record.

How well do you think bitcoin lives up to that?

I think [Satoshi’s] done a great job, but it’s just a particular application. Vitalik [Buterin] comes along and says, “Well, this shouldn’t just be about money. I read Nick Szabo’s paper, and we should incorporate smart contracts, and we should have a general purpose computing machine.” I think that’s a great idea, but I think that he drank too deeply from the bitcoin view. That, I think, has constrained Ethereum a little bit.

How would you suggest he go about building Ethereum in a way that departs more from bitcoin?

It’s not my place to tell other people how to do their research, but I think there are lots and lots of people exploring this space. It’s a space I would describe as threefold. But first, we have to establish a set of cryptographically interlinked records that are widely distributed. That’s the baseline—an immutable foundation. Then there are three dimensions to explore built on that foundation. One, where and what computation should we be doing? Two, what incentives need to be offered to keep the system operational? And three, how should consensus be achieved?

Going back to when you and Stuart used the New York Times to publish customer hashes as part of the time-stamping service you offered at Surety—I’m wondering, are there any use cases today where an at least partially analog blockchain would be more useful than a fully digital one?

The first thing I want to emphasize is that the concept of embedding the document in the New York Times, which was widely published, is not truly essential to the idea. What’s essential to the idea is that the people who wanted the service became holders themselves of part of the record.

It’s that community of people that have an incentive to hold the record that is the essence of the blockchain. In a sense, Satoshi creates an artificial community. I don’t mean artificial to be derogatory to him. He’s creating an artificial community by creating the mining incentive. All we really need to do is have a self-sustaining system where there’s an incentive for users to naturally want to hold the record for their own self-interest, which benefits others using the system. In that regard, there are lots of examples of historical blockchains that predate the digital world.

Like what?

Apparently, there’s a true historical event where two neighboring tribes had a dispute about their boundary. They came together and agreed on where the boundary would be, and as a memorial to that, they put together a pile of rocks. Then the community had a ceremony where they all witnessed their agreement. Right there, you have the essence of the blockchain, because you have an event that is widely witnessed and memorialized as a shared view of the world. That’s what the blockchain is.

I was very intrigued by the analog aspects of your early ideas about time-stamping. You also brought up the option of writing a letter, mailing it to yourself, and keeping it enclosed in the envelope to show that it was written before a certain date. Are there other methods like that that you think are maybe better or just as good as a digital immutable ledger?

On that front I would say no. But here’s the thing—you keep talking about analog, a-n-a-l-o-g, analogues, a-n-a-l-o-g-u-e. Fundamentally, it’s not the protocol that is the essence of the solution. It’s the organizing of society via the protocol that creates a consensus. All of the analogues are really about us as people and how we relate to each other. If people are looking for advice, technology can provide solutions, but the key is to make sure that you’re solving the right problem. The key is to have good taste in recognizing what is possible in social relationships at large.

I feel like social relationships are what a lot of blockchain projects are struggling with now. For example, people involved in Ethereum are really trying to get something done as a community, and it’s caused some issues…

People go a little sideways [by thinking], “Community has to be the solution, now let’s a find a problem.” You can’t do that. You have to sneak up on a problem on its own terms. You have to try to think what the real essence of the problem is before throwing a particular piece of technology at it, or concluding that community has to be the answer. I’m making a distinction between community and solving problems about the inner relationships among people.

Since we were talking about Ethereum, would you define a specific problem there?

This is nothing against Vitalik or Joe [Lubin]. I question whether what the world wants is a universal computer. I think it’s clear to me that the world definitely wants a universal record, and that it wants to be able to perform computations on that record, but I’m not quite sure that the alignment is perfectly right. Having said that, please understand, we’re all just poking around and trying to figure out how to get this right. Ethereum is a huge advance, and it stimulated all sorts of other thinking. I’m not suggesting that it’s bad. It’s just, we’re not there yet.

I’m curious about your thoughts on the blockchain communities that rely on consensus or voter majorities and basically trust in other individuals, because when you were trying to disprove the possibility of an immutable ledger, you had to deal a lot with ideas about people trusting each other.

Again, without meaning to be critical, my general observation is that they are focusing a little prematurely or overly much on the trust mechanism for solving a general problem. They would be more likely to prosper if they could apply their ideas to a particular problem.

Do you have any thoughts on the best way for a group of people to get together in a room and make sure that they trust each other? Say they’re all guarding treasure together, and they have to trust each other not to steal it.

I kind of like the Panopticon inverted. It’s a circular prison with glass walls so that you can have a couple of people in the middle keeping an eye on a very large group of people. I think the problem you’ve posed needs a reverse panopticon. Namely, the community is on the outside, and the treasure’s in the middle.

Is there a digital system you could translate that to?

Fundamentally, you have to create a set of incentives that is self-sustaining. Very clearly that is what Satoshi was attempting, and it was a bold attempt. It was a bravura performance. But getting those incentives right is very, very hard.

It seems like money is what most people come up with.

That is because money is a universal medium of exchange. You have an idea of what you think you want, and much of it can be purchased with money. Although, there is a declining effect. After you have a certain amount of money you start to find that it’s preventing you from getting what you want. You’re right—it’s a universal incentivizer. If you read Adam Smith’s The Theory of Moral Sentiments, you find that what people really want is people that will empathize with them. It’s creating a set of empathetic self-interest that is where an important solution lies. And, I might just mention in passing, we’re working on that problem at Yugen.

Well, since you mentioned it, tell me more.

All I can tell you at this point is that the project is currently called Gazillion. The reason we chose Gazillion as a name was to make it clear that Google was not the only big number.

Fair enough. At Yugen, what kind of projects do you point investors toward?

There are a number of [types of projects]: improving the integrity and transparency of existing corporations, improving the efficiency of systems of organizations that interact with each other, including in the financial services industry, just to be a little bit concrete. We think there are opportunities in creating assets that are more liquid, so that they are more broadly available to others. I think creating social systems with token-based economies built on blockchain-based incentives are very promising, and I think systems that tend to distribute capital and the benefits of participating in the systems more evenly among people are also promising—that’s five areas.

Are there any particular projects that really excite you that are happening in the blockchain space right now?

There are things that we are starting to place investments in. Those will be more public information shortly. We’re not trying to be coy for the sake of being coy. I’ve identified five areas, and I think you’ll see us putting our money where our mouth is.

My very last question: Who do you think Satoshi Nakamoto is?

[Pauses.] Yeah… [Stornetta covers his face with one hand.] I think I’m not going to respond.

This interview has been edited and condensed. Main photo courtesy of W. Scott Stornetta.